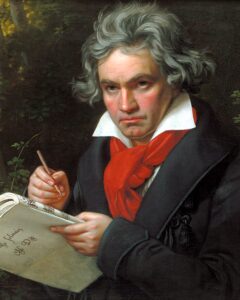

Is it Fate knocking at the door, or did Ludwig Van Beethoven have something else in mind entirely when he penned the startling opening notes of his famous “Symphony No. 5?”

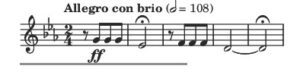

Is it Fate knocking at the door, or did Ludwig Van Beethoven have something else in mind entirely when he penned the startling opening notes of his famous “Symphony No. 5?”

Those three notes, then one: G-G-G, E-flat. Repeated one step down as F-F-F, D, and the stage is set in suspense for classical music’s most famous symphony.

Audiences will have a chance to hear those notes and feel the suspense once again as the Louisville Orchestra presents Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5” in concerts January 13 and 14 in Whitney Hall. The concerts also include Beethoven’s “Piano Concerto No. 5,” with pianist Leonard Biss, in a program the symphony is calling “Fifths of Beethoven.”

Also on the bill is a new work by Lisa Bielawa, a composer in the symphony’s new Creators Corps. Music Director Teddy Abrams has the baton.

Now, if you’ve got your piano handy — or an old clarinet, or even a smartphone with a keyboard — here are the top notes of the chords that open the fifth symphony. Give it your dramatic best, and memory might take over with violins off and flying, and four French horns asking the “fateful” question again.

It’s a heckuva start, and just the beginning of a symphonic journey that ends in even more suspense and a final triumph.

But is it Fate knocking at the door?

That’s the story advanced by Beethoven’s secretary Anton Schindler in a biography published in 1840, 13 years after the composer’s death. Schindler recalls the moment: “Beethoven expressed himself in something like vehement animation when describing to me his idea, ‘It is thus that Fate knocks at the door.’ ”

But Schindler’s reputation has since been tarnished, with succeeding historians noting that he kept and hid some of Beethoven’s diaries. They suggested that Schindler was most interested in glorifying his closeness to greatness.

On the other hand, he was there.

Matthew Guerrieri, the Boston Globe music critic and author of the “The First Four Notes,” told NPR host Robert Siegel that nothing is settled on the notes’ meaning.

“This is probably an invention of Beethoven’s biographer, though we really can’t tell,” says Guerrieri. “The other story going around at the time was that Beethoven had gotten the opening motif from the song of a bird. That story just sort of fell away as the fate symbolism took over. But in Beethoven’s time, and to Beethoven, (who loved to walk in the countryside outside Vienna) a bird song would actually have been a fairly noble way of getting a musical idea.”

Most important, of course, is the music, with Beethoven as the landmark composer of the Romantic Era. It was a “Romantic” notion that a composition could express abstract ideas and emotions, like love and joy and grief. (And maybe the suspense of fate knocking at the door.)

“The whole idea that music picks up where language leaves off — which is pretty much a cliché nowadays — that was a very specific Romantic idea, and one that lasted,” says Guerierri.

V for victory

John Eliot Gardiner, Director of the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Rommantique, has another idea.

“The way I approach the fifth symphony’s opening movement,” says Gardiner, “is via the French Revolution, which Beethoven was very caught up in at the time, and the music associated with the French Revolution, (including the words) of that particular hymn Les Marseillaise: ‘I will die, sword in hand, for the rights of man and the glory of the Revolution and the Republic.’ ”

It’s not a far-fetched notion. Beethoven was an avid reader of Rousseau and Voltaire, and a believer in the ideals of the French Revolution, the rights and dignity of man. (Though he dropped his admiration of Napoleon when the French leader crowned himself emperor and invaded Austria. More on that later.)

Another story from the fifth symphony is how Beethoven’s opening notes found their way into World War II.

The story goes that Resistance fighters in Belgium in 1943 used the letter “V” in graffiti markings as communications. V was “Vrijheid” for freedom in Flemish, or “Victoire” in French for victory. In England, the BBC picked up on the V, and broadcast it in Morse Code, with three shorts and one long — dit-dit-dit dah— signaling a coming coded message from the Allies to resistance fighters in Europe.

It wasn’t long before someone at the BBC realized that the Morse Code signal “dit-dit-dit dah” fit perfectly with Beethoven’s G-G-G E-flat.

Of course, the American painter and inventor Samuel F.B. Morse (1791-1872) probably wasn’t thinking of the fifth symphony when he assigned the dots and dashes for “V” in his code.

Or was he?

The epic 1962 movie “The Longest Day” employed the Beethoven opening to great effect in setting the D-Day scene of the Normandy Invasion in the Allies’ World War II struggle to retake Europe from Germany. The notes are rivetingly effective in a scene at dawn with thousands of ships and planes — as far as the eye can see — coming across the English Channel in the invasion of France on June 6, 1944.

Fate knocking at the door?

But with all the attention on those opening notes, they’re just a wisp of the might of the fifth symphony.

Even more exciting is the way Beethoven’s fifth symphony unfurls through the third and fourth movements. There is no stop between the movements, as the third winds down in a long, long (about 43 measures) cascading descent of notes that climaxes in a towering plume of triumphant chords.

Beethoven adds trombones and a contrabassoon to the orchestra to create those sensationally deep chords, with piccolo piping atop.

Fate knocking at the door? Well, come on in!

‘Piano Concerto No. 5: The Emperor’

If the fifth symphony has drama, so too does the fifth piano concerto.

Dennis Hallman, a former Louisville Orchestra horn player, recalls attending a performance of Beethoven’s “Piano Concerto No. 5,” with the noted pianist Rudolph Serkin.

“I was seated next to a father and his young son,” recalls Hallman. “At one point, the music is getting softer and softer, and Serkin is taking things down and down in volume, to almost a whisper. The father nudges his son with an elbow, and whispers, ‘He’s getting ready to lay into it.’ ”

And of course, Serkin did lay into it, just as Beethoven would love.

Because it’s that kind of piece. Beethoven was opening up the power and scope of the piano, his own instrument. And giving the soloist the musical nod to lay into it. Or lay off.

The piano was not an ancient instrument in Beethoven’s time. It was just then evolving as a “pianoforte” from the limitations of the harpsichord. The harpsichord has a keyboard, but is a plucked instrument, with keys connected to levers that pluck strings, as the strings of a harp would be plucked. A nice sound. But only one volume. And not much volume, at that. Best suited for a music room and a small “chamber” audience.

The piano, however, has keys that connect to levers with mallets that hammer the strings. It is capable of the widest range of dynamics, from a light-fingered touch sounding a soft piano, to a hard touch hammering a forte. Thus the original name, pianoforte.

The piano was invented by Bartolomeo Cristofori in Italy around 1700. In the century to come, the instrument evolved through a series of inventors in Germany and England. J.S. Bach tried out a piano, and one of his sons played another, experimentally.

A key development was the addition of a steel frame to support a heavy wooden cabinet and strong soundboard. Mozart loved his improved version, and Beethoven performed on an even better one. It was Beethoven’s notion that the piano could step forward from being played in the company of a few other instruments to take its place on stage with a symphony.

And about that name on the concerto: “The Emperor.” Beethoven had nothing to do with that. A later music publisher stuck it on.

Beethoven had the fifth concerto ready to go soon after the debut of the fifth symphony in 1808. But Bonaparte’s French army placed Vienna under siege, and its citizens took cover. Beethoven spent much of that year sheltered in a basement. When the French bombarded the city, he held pillows to his ears to protect what little remained of his hearing.

When the shelling ended, the concerto was premiered. The composer had long ago disavowed the emperor. The concerto ruled majestically.

Fate, indeed.

For more information about the Fifths of Beethoven performances or to purchase tickets, visit louisvilleorchesta.org or call 502-584-7777.

Article written by Louisville’s-own, Bill Doolittle