Cutting sugar cane in Louisiana. (1909-1913) From the collection of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library.

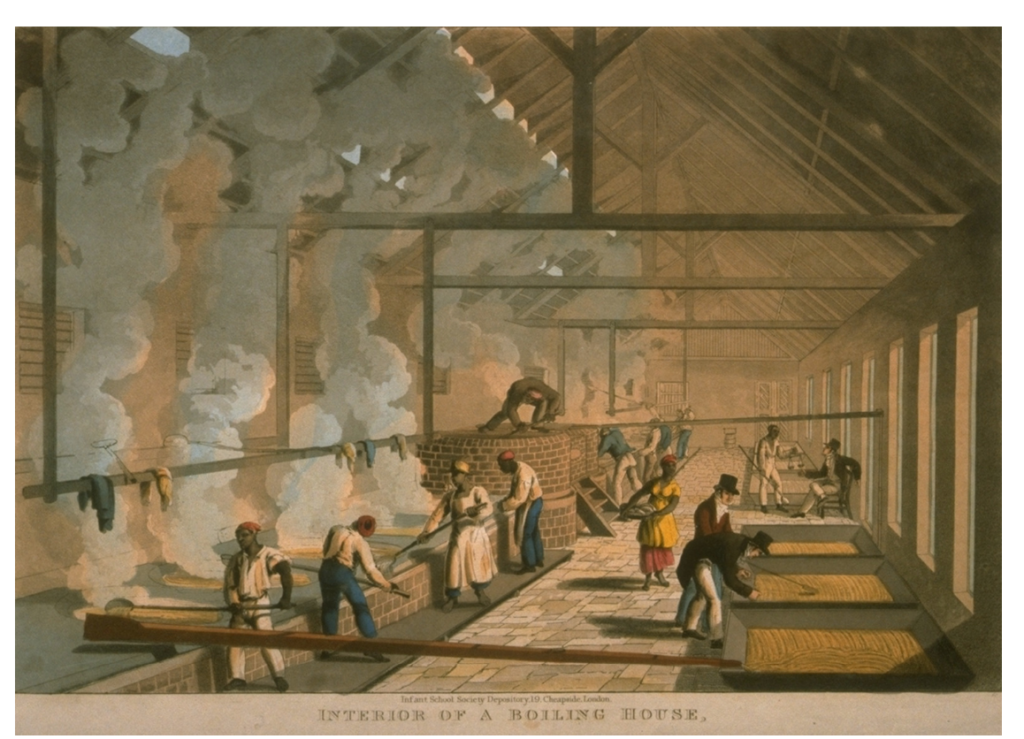

The Speed Art Museum is excited to open a new exhibit to ring in the New year. The Bitter and the Sweet: Kentucky Sugar Chests, Enslavement, and the Transatlantic World 1790-1865 will run through April 7th and boldly reexamines the Kentucky sugar chest and related objects within the broader, intertwined contexts of the Atlantic economy, the vicious human toll of enslavement, and the complex transportation systems that brought sugar to Kentucky from the West Indies and sugar-growing regions of the Americas.

Skilled Kentucky cabinetmakers used local materials to create these highly specialized furniture pieces to store costly refined white and brown sugar that was grown and harvested by enslaved men, women and children. Taking a closer look, visitors learn that the backstory behind these beautiful pieces isn’t as gleaming as the polished silver or glimmering walnut and cherry items the museum has on display.

Sugar Desk (1810-1840) made from cherry, poplar and other woods from the Noe Collection as a gift of Bob and Norma Noe, Lancaster, Kentucky.

“It’s important to place these objects within a deeper and more meaningful historical context to show why these pieces of furniture exist in the first place. I think many people are unfamiliar with how deeply involved enslaved people were in the growing of sugar and how sugar became a global desire,” said Jennifer Downs, the Speed’s Terra Foundation Assistant Curator.

Prominently displayed in Kentucky parlors or dining rooms, a fashionable sugar chest reflected the wealthy status of its owner, and supported social rituals such as coffee, tea and alcohol consumption, which further showcased and reinforced prosperity. However, “not everyone could afford to purchase sugar in quantities large enough to require a specific piece of furniture to store it,” she said. The powerful nostalgic sentiment that has long been associated with utilitarian sugar furniture, which often incorporates fanciful and regionally specific decoration, contradicts the history of the sweet substance it was made to store.

A sugar boiling house in Antigua, West Indies representing the sugar making process. (1823) From the collection of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

“It is vitally important for museums to address the complicated histories of many objects in their collections and reframe objects within more inclusive contexts to reflect the diverse communities that they serve,” said Downs.

Housed in the museum’s Kentucky Gallery, The Bitter and the Sweet is viewed as a first-of-its kind hybrid art-and-history exhibition that features a variety of media, including sugar furniture, related objects, contemporary artwork, archival materials, 19th century tools and video material.

For more information, visit SpeedMuseum.org