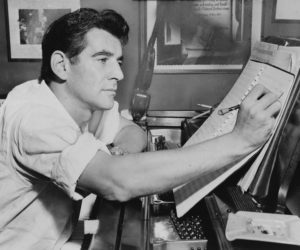

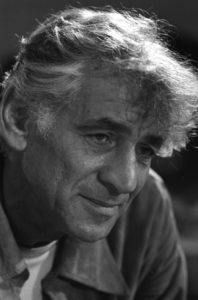

As we celebrate his 100th birthday— nearly thirty years after his death—it is an occasion to muse about how history will treat Leonard Bernstein. In an era of increasing specialization, he was an artist of many talents: a pianist, conductor, composer, writer, educator and musical ambassador-at-large. This is almost without parallel today—few artists become so highly skilled at so many disciplines of their craft. There are even fewer who could master so many genres within their purview, as Bernstein did with classical, jazz and popular music, sometimes combining them all at the same time.

We are thrilled to celebrate Bernstein at 100 on Saturday, September 29th at The Kentucky Center – Whitney hall. Teddy Abrams will be the conductor with vocals from Morgan James. For tickets and more information, visit LouisvilleOrchestra.org

Bernstein also had the uncanny ability to walk into a room full of non-musicians and in fifteen minutes have everyone around him excited about music. As a composer, Bernstein will no doubt be remembered for bringing high-class music to the Broadway stage in West Side Story, a musical interpretation of Romeo and Juliet that is as tightly constructed as any opera by Mozart. And his film score to On the Waterfront is one of the greatest ever written. His symphonic music still awaits the judgment of history, but it amply repays our attention in the here-and-now.

We were uncommonly lucky to have him; for many musicians who came of age in the Bernstein era, it’s still hard to believe he’s gone. His music will live on, of course. But what to make of that music, in its exuberant and flamboyant diversity? The scrutiny of any one piece by Leonard Bernstein is like viewing a fleeting snapshot from an expansive and eclectic career: it tells you little about the man himself, only what he looked like at the moment. To his colleagues, to his students, to those who knew him—both riff-raff and royalty—he was Lenny, almost as indefinable as his music. He was a man in full, and full of humanity. There were many threads that wove their way through this musician’s life and music, but perhaps the strongest was love. The love of his art, to be sure, but also his undying love for his fellow man. The last line of his Chichester Psalms said it all: “Behold how good and how pleasant it is, for brethren to dwell together in unity.”

Leonard Bernstein was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1918 and died in New York City in 1990. He composed his operetta Candide in 1955–56, and the first performance took place in New York in 1956 under the direction of Samuel Krachmalnick. Bernstein revised the work in 1988. The first performance of the Overture as a concert piece was with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of the composer in 1957. The score calls for 3 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 4 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp and strings.

Leonard Bernstein was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1918 and died in New York City in 1990. He composed his operetta Candide in 1955–56, and the first performance took place in New York in 1956 under the direction of Samuel Krachmalnick. Bernstein revised the work in 1988. The first performance of the Overture as a concert piece was with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of the composer in 1957. The score calls for 3 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 4 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp and strings.

Candide never found a large audience, but the Overture, laced with tunes from the show, was instantly popular and has become the most widely performed piece by Bernstein. It opens with a brash fanfare for the brass and percussion that leads right into an incredibly off-kilter theme from the wedding of Candide and Cunegonde—a frenetic ceremony interrupted by a war in Westphalia. The warm and lovely tune that follows in the low strings is “Oh, Happy We”—a love duet in seven beats to the bar. After a reprise and a full stop, we hear the music from the song “Glitter and Be Gay,” for which the term “perky” must have been invented. Those who are of A Certain Age will recall this as the theme music for Dick Cavett’s television show.

If orchestral music can “glitter and be gay,” the Overture to Candide surely does. In a mere four minutes it is witty, tender, exhilarating, spectacularly colorful—and an orchestral tour de force that is devilishly hard to play. A better curtain- raiser was never composed.

Bernstein began a work called Lamentation for soprano and orchestra in 1939; this became the final movement of his First Symphony, completed in 1942. Bernstein conducted the first performance with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in 1944. The score calls for mezzo-soprano, 3 flutes, piccolo, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, piano and strings.

Bernstein once said that all of his large works share a common theme: “The struggle that is born of the crisis of our century, the crisis of faith.” And not just religious faith, but faith in the individual, faith in mankind, faith in the future. All three of his symphonies deal with this question, and each comes to a different conclusion. The First is the “tragic” symphony of the set, for it is a lamentation on the loss of faith, and how that loss is self-inflicted.

In the first movement, Prophecy, the prophet Jeremiah warns the people of the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple. It begins darkly, builds to an intense climax, and then dies away, for the prophecy goes unheeded.

The second movement Profanation is the work’s scherzo; the people and the corrupt priests mock the prophet and carry on their noisy and sometimes violent desecration’s.

As the third movement begins, Jerusalem has been destroyed, and the mezzo soprano sings (in Hebrew) from the Book of Lamentations: “How doth the city sit solitary…how is she become as a widow?” And, finally, “Wherefore dost thou forget us forever, and forsake us so long a time?”

As the third movement begins, Jerusalem has been destroyed, and the mezzo soprano sings (in Hebrew) from the Book of Lamentations: “How doth the city sit solitary…how is she become as a widow?” And, finally, “Wherefore dost thou forget us forever, and forsake us so long a time?”

It is possible to see the work as a large sonata form, with the three movements representing an exposition, development and recapitulation. This is all the more true because Bernstein, with this work, began the practice of deriving his new themes out of preceding ones. He said that the symphony “does not make use to any great extent of actual Hebrew thematic material,” though it is there to be found if one looks for it. As to its programmatic meaning, he said, “The intention is not one of literalness, but of emotional quality,” especially in the first two movements. The finale, he said, “is the cry of Jeremiah, as he mourns his beloved Jerusalem, ruined, pillaged and dishonored after his desperate efforts to save it.”

Don’t miss the Bernstein at 100 on Saturday, September 29th at The Kentucky Center – Whitney Hall. Teddy Abrams will be the conductor with vocals from Morgan James. For tickets and more information, visit LouisvilleOrchestra.org